from Cinegraphic.net:

"Beyond Spatial Montage" part 2 of 6

story © Michael Betancourt, November 10, 2014 all rights reserved.

URL: https://www.cinegraphic.net/article.php?story=20141104073729961

This theory work will be published as a book-length monograph Beyond Spatial Montage: Windowing, or, the Cinematic Displacement of Time, Motion, and Space by Focal Press.

Part 2 of a 6 Part series proposing an expanded theorization of spatial montage, excerpted from a current book project.

The technologies of compositing and image combination directly contribute to the development of juxtaposed imagery. While the production of composite imagery is evident in the history of motion pictures since the first Trik films were made in the 1890s, the relative rarity of these images—even within the Trik film—remained relatively constant due to the difficulties of their production. The greatly reduced costs, coupled with relative ease of production with digital video has made the integration of live action, animation and graphic design via compositing a common feature of motion graphics and commercials even though it remains relatively unusual in narrative production.

The distinction between different potentials within the range of these forms is a function of the on-screen affect of the materials combined. For narratives with live actors and edited sequences of shots, these potentials have a more limited application. The apparent division and fragmentation of the screen into smaller, discrete units in narrative works remains unusual even as similar forms appear more frequently in the commercials and title sequences accompanying these realist fictions.

This heuristic composited, juxtaposed imagery is taxonomic in nature, empirically developed from studio-based research, historical observation and logical analysis. These limiting factors give the resulting framework a robust basis in practical application—observational and descriptive, the taxonomy enables the recognition of mutually interrelated positions. This organizational framework is not dialectical in nature. The logical completeness the taxonomic form proposed in this analysis allows for both extension and hybridity specifically through its heuristic application. The significance of the forms it describes, their meaning, is not only a function of formal structure. It depends on the specifics of the imagery and its temporal development with a larger work. While the formal organization on screen may be decisive in this interpretation, its role is necessarily secondary to the particulars of image, development, and narrative function: meaning is not an a priori given in the resulting semiosis.

Ambivalence and ambiguity are common features of purely formal analysis that develops independently of hermeneutic constraints. This uncertainty is precisely the goal in the current analysis. The description of formal structures in themselves should not result in inherently appended meanings, since to attach signification requires the exclusion of alternative potentials; thus necessarily limiting the analysis only to evidence that supports a determinant meaning within a specific logical structure.

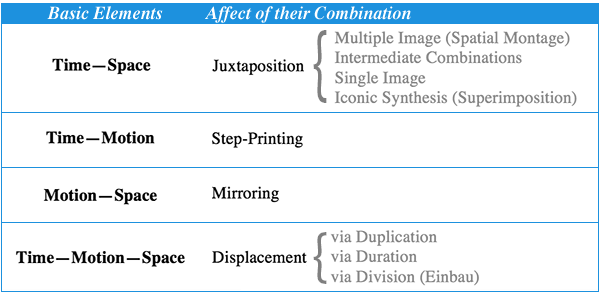

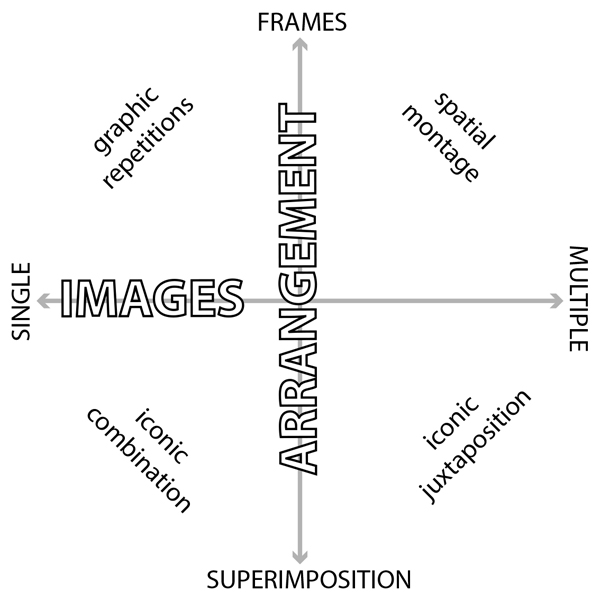

Time—Space Displacement

The morphology of Time—Space displacement is a complex matrix of potential relationships: the quantity of single- and multiple-images that are juxtaposed, and their spatial relationship either as discrete units within a larger frame, or iconically as the entire frame itself. The morphology of these forms within this field is arranged between from structures of maximal difference towards structures composed by similarity of imagery. The morphology of juxtaposed images is not a matter of the distinctness of individual ‘subframes’ within the composition, so much as it is an issue of whether these images have the affect of displaced imagery. Affect is crucial—the audience identification of one pair of composited or superimposed images as being juxtaposed, and another pair as being a single, continuous image without juxtaposition is sufficient to distinguish between those shots that employ Time—Space displacement and those that do not even when both employ superimposition or compositing.

The matrix of potentials in this type of displacement reflects the degree and quantity of images on screen, as well as their differences with each other: the simplest forms of Time—Space displacement are described by “split-screen” where two shots play at the same time and superimposition where two shots are overlaid onto each other. Both forms emerge by 1910, employed by Emile Cohl in his animations; the distinction of Cohl’s uses from Time—Space displacement depends not on their technique of production, but on how the audience understands them as being continuous, singular shots—effects reinforced by the composited shots’ role in his narratives (c.f. The Next Door Neighbors where the two adjacent rooms are understood to be spatially linked even if their imagery is not).

These formal effects are uniformly developed in motion pictures whatever their technologies might be. Video art explored many of these effects using analog technology, independent of the demands posed by realist cinema; for narrative cinema, this form is commonly employed to display simultaneous events at different locations on screen at the same time. This presentation of simultaneous events simultaneously is the most familiar type of Time—Space displacement because it has been the most frequently used narrative application—one that meshes with the demands of realist cinema most completely. The continuity of duration in these dramatic narrative applications reinforces this realist use by employing long takes in the variously windowed compositions, whether as a simple pairing in “split-screen” or as a much more complex arrangement with multiple shots positioned on screen.

The range of Time—Space displacements described below are extreme positions within a spectrum of possibilities that have intermediate and overlapping examples, rather than mutually exclusive structures. Distinct approaches can be distinguished by their subject matter: one employs a singular subject shown multiple times (potentially from multiple viewpoints), while the other combines different subjects, juxtaposing their imagery on screen in a graphic fashion. he spatial displacement of imagery (typically individual, discrete images) creates juxtapositions and relationships between the images that enables a narrative understanding of them as coincidental. The distinction between the two variants of this approach depends on the materials being combined—one employs a single image in a graphic fashion, repeating it without a temporal displacement on screen; the other composes multiple, different images on screen at the same time.

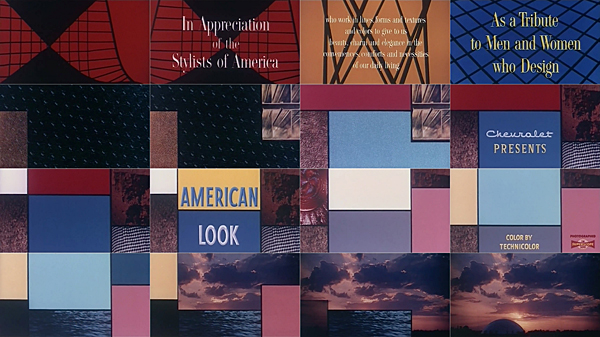

Multiple Image Juxtaposition (Spatial Montage)

The juxtaposition of Time—Space displacements emerge from the collage-like arrangement of discrete images of multiple, different subjects together on a printed page; it was formally developed by magazine paste-up, advertising, and graphic design. This variety of windowing has received the most theoretical/critical discussion. These works are specifically composed from multiple, discrete, independent images that have been assembled on screen to create juxtapositions of material. Formally linked to the multiple screen presentations of expanded cinema and video art, spatial montage is displacement based in juxtaposition of several images, typically of different subjects coexisting side-by-side, each discretely bounded and arranged together (often) following a rigid grid.

Stills from the title sequence for American Look, designed by Robert Mounsey, Charles Nasca and Otto Simunich for Chevrolet (1958).

The displacement of spatial montage have an entirely different affect from the displacements common to the Cubist-derived morphology created by repetition. Historically spatial montage has been difficult to produce, requiring either an animation stand or the optical printer’s compositing capacities, making it both expensive and comparatively rare. Their appearance in newsreels that were already heavily using optically printed sequences is one of the few places where this type of multiple image juxtaposition and compositing was common. With the ease of compositing with digital tools the graphic juxtaposition of discrete moving images distributed across the frame as individual spatial fields has become much more common.

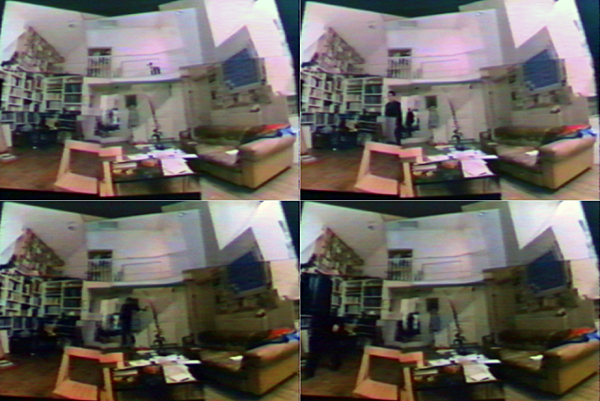

Intermediate Combinations

Intermediate positions between multiple image works juxtaposed on screen and works with singular repeated shots arranged graphically are possible. A single subject filmed multiple times, perhaps from a variety of similar angles, or even from the same fixed position multiple times, can be presented in an arrangement where the result is clearly a Time—Space displacement, but the affect is not juxtaposition but is instead related to repetition without being the strict reproduction of identical shots. These works are fundamentally linked to the historical, fragmented structures of Cubist painting.

Stills from David Hockney’s "experiment with film" produced for the documentary Portrait of an Artist: Hockney (1983).

These displacements are focused on a single space/subject that is then subject to being presented through an array of multiple views, coexisting and simultaneous, and it is this singularity of subject matter that distinguishes the first variation from the second.

Single Image Juxtaposition (Graphic Repetitions)

Repeated imagery composed and arranged on screen produces a Time—Space displacement but does not require the production of multiple long takes: it repeats a single shot, and uses it multiple times, forming complex arrangements that juxtapose identical imagery. The simplest variants of Time–Space displacement transform a singular image to create a pattern of identical elements typically composed in a grid. Of the two potentials for Time–Space displacement, repetition commonly employs single images rather than collections of divergent imagery; the spatial repeating of the single shot creates a continuous field of imagery that acts to emphasize the graphic character of the image rather than the uniqueness of visual contents. Juxtaposed imagery is secondary to the continuous pattern formed.

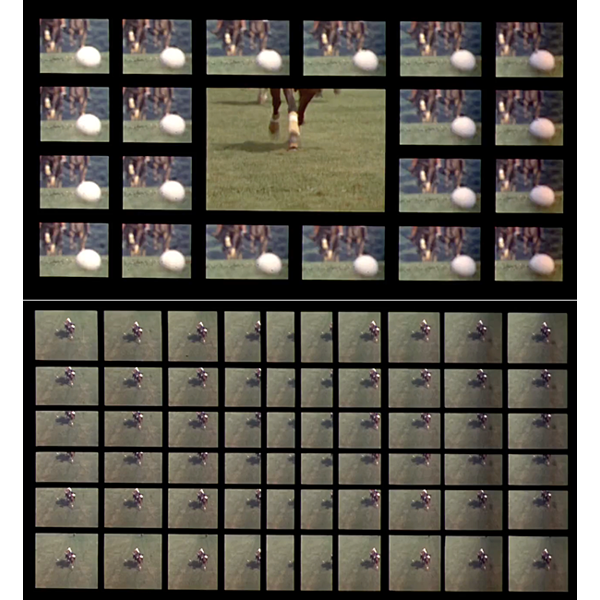

Stills from The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) showing repeating imagery in the "polo sequence" designed by Pablo Ferro.

The graphic repetition of identical shots is the focus of this subvariant of Time—Space displacement. Grouping similar actions on screen within unrepeated montage or dynamically in complex compositions in both cases remains subservient to the narrative demands imposed by their context. This narrative function is determinant of both formal organization on screen, selection of imagery to repeat, and the meaning those repetitions have. While these applications are linked to graphic design, in particular the Modernist advertising design of the 1950s and early 1960s, in a motion picture their function (narrative role) dominates their construction. This subservience to narrative is a common feature of commercial uses for the full range of Time—Space displacements.

Iconic Synthesis (Superimposition)

Still within the realm of juxtaposed imagery, but distinct from both the single shot subjected to graphic repetition, and multiple framed images composed in a spatial montage is the iconic image created by superimposition. There are two variations of this iconic construction: those produced by multiple image combinations superimposed over each other (iconic juxtaposition), and those produced by single images superimposed over themselves (iconic combination) and functioning as intereference patterns. The production of these iconic images is uncommon in the history of motion pictures. While the superimposition has been possible since the beginning of cinema, appearing in “Trik Films” as a technical strategy during the 1890s, the Time—Space displacement appearing in these shots only seems slight: it is produced by the audience’s recognition that these shots would not normally be possible—that there is no potential for these images to be the product of an unmanipulated long take. Thus while the technique of superimposition is quite antique, the affect it must have must be one where the imagery combined creates a visual synthesis, rather than being a realist combination of images to produce the illusion of a singular continuous shot.

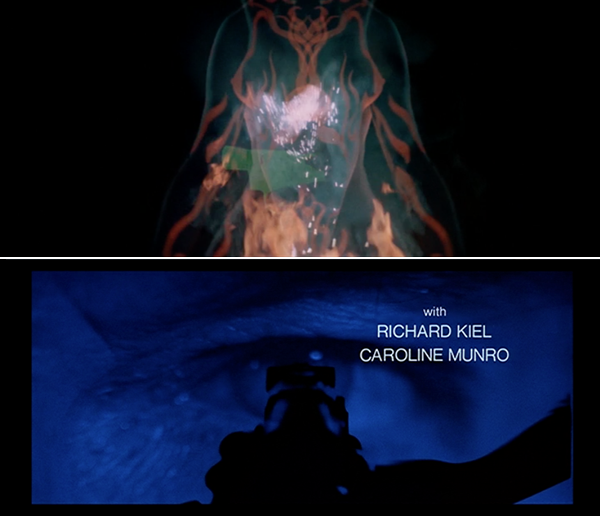

Stills showing iconic synthesis: (top) A View to A Kill (1985) designed by Maurice Binder showing an dancer producing an iconic combination; (bottom) from The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) designed by Maurice Binder showing eye-gun iconic juxtaposition.

The same set of potentials appearing in discretely framed compositions apply to the full-frame superimposition: compositions juxtaposing both single imagery and multiple imagery can be produced as full-frame superimpositions. The distinction of these effects from the use of superimposition in long takes depends on the affect these combinations have: they do not produce a seamless continuity, instead generating their form through the contrast between the images used. Even when a single shot has been doubled onto itself, it must have the visual effect of being displaced, rather than an illusory combination that asserts the continuity of the singular image; this simple distinction enables the separation of superimposed elements within a long take that function as realist continuity and the superimposed elements that result in a dislocation of imagery. The creation of ‘iconic’ imagery through superimposition is a common feature of both advertising and title sequence design.

The subservience of Time—Space displacement to narrative is the common application for these structures, whether they juxtapose, repeat or otherwise combine imagery on screen. They enable the presentation of simultaneous actions as happening in congruent spaces on screen without the need for cross-cutting or the traditionally parallel editing that conveys the same information sequentially. By allowing the presentation of simultaneity in a continuous fashion on screen, the Time—Space displacement recreates the affect possible on the nineteenth century theatrical stage: the presentation at different points on stage of simultaneous events. In this regard, the collage-like features of these images are secondary to their capacity to create spatially discrete points of contiguous action on screen; the combinatory potentials juxtapositions offer in avant-garde film, for example, is a minor development parallel to the primary, narrative application in commercial cinema. This narrative function is so dominant that the earliest examples of juxtaposition produced by superimposing two shots on the same film strip, at once familiar and antique, is difficult to recognize as belonging to this range of Time—Space displacements.

Beyond Spatial Montage:

Part 1 Foundations

Part 2 Time—Space Displacement

Part 3 Time—Motion Displacement (Step Printing)

Part 4 Motion—Space Displacement (Mirroring)

Part 5 Time—Motion—Space Displacement

Part 6 Afterword

Copyright © Michael Betancourt November 10, 2014 all rights reserved.

All images, copyrights, and trademarks are owned by their respective owners: any presence here is for purposes of commentary only.