from Cinegraphic.net:

observations on my process

story © Michael Betancourt, February 25, 2022 all rights reserved.

URL: https://www.cinegraphic.net/article.php?story=20220225124106908

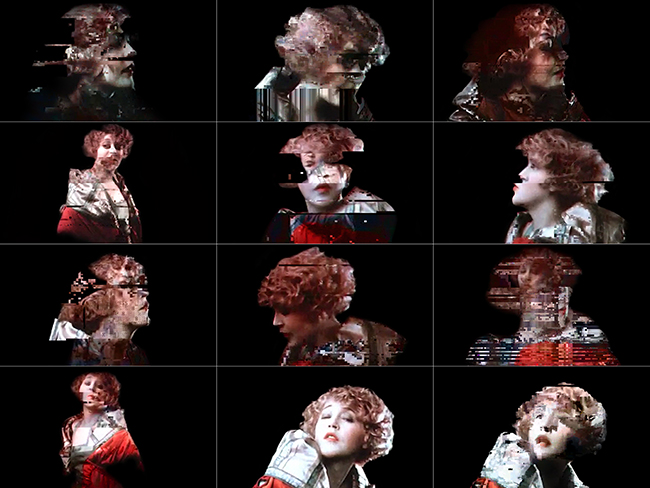

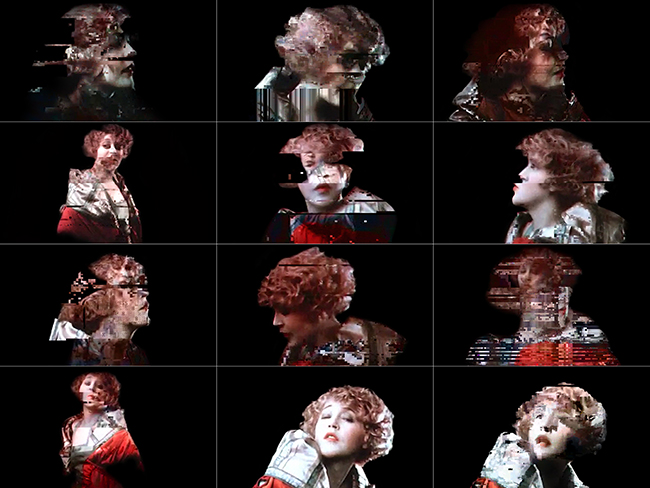

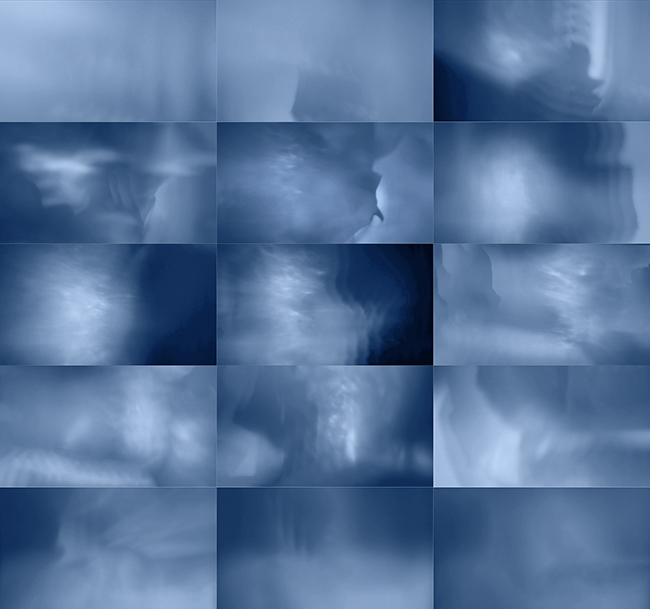

I make “Glitch Art”; my work pioneered this engagement with digital computers in the 1990s before it even had a name. The role of autonomous and automated systems in my work makes the question of ‘my process’ something that can be difficult to articulate clearly. The way I understand these generative images as simply another category or type of footage, one that is abstracted, but is neither necessarily critical nor essentially ‘broken’ shapes how I use it as both a formal model to emulate with the non-glitched, and as an abstracting protocol to employ against the photographic realism that might otherwise emerge in my movies. Those ‘intentional’ factors constrain the glitched materials so they become cues for their audience that what they see is not merely a malfunction, but is consciously shaped and chosen. The glitch is a pervasive, even dominant, contemporary sensibility for all the ruptures, aberrations, transformations that technical processes create—becoming manifestations of our interactions with the world.

‘Process’ is not the same as ‘processing.’ The former is a continuously interrupted and delayed action, performed as a kind of feedback done in the studio that tries to adjust perception to align with intention, while the latter is autonomous, the role operations performed by machines according to a set program. Very different things, yet clearly connected: without process, there is no processing—the implementation—but when working with autonomous machines, (although this range includes computers, it also includes the analogue film camera), and their capacities for automation and precise control over outputs, the distinction of process and processing blurs the boundary between the artist’s actions and their art. If one rejects or questions that idea that cinema can function as a metaphor for interior experience through the abstraction of the image, then what remains to consider in terms of ‘process’? This question is something that my work constantly returns to though the role of automation in generating my images, i.e. via glitching, but the idea of cinema-as-metaphor is deeply ingrained in the aesthetics of “avant-garde cinema” and is one of the reasons for its fetishing of celluloid in opposition to electronic video and digital technologies. For me, concepts developed by visual semiotics provide an answer to this problem or expressive organizations, but this solution works against concerns with authorial intention or questions of process, replacing them with commonalities of perception and their affects—which in my work move within a range where the realism or abstraction of any given image is ambivalent. It is also the reason my discussions of process are rarely satisfying for those concerned with expressive/intuitive “genius.”

The dictates of authorial intention have always been problematic for my process, something that has consistently given me pause within my process; as a means to escaping from my own restrictions and assumptions about how to proceed, in 2008 I bought a stack of blank playing cards and started writing ambiguous, but precise instructions on them (I published them as the Eupraxis Media Art Procedures deck in 2012, and reprinted them in 2015 when the first edition sold out). These stoppages were taken directly from my book Structuring Time, a compendium of notes and formal observations about motion pictures that I began collecting while I was in graduate school as a way of breaking with the dominant formalist approach I was encountering in the classroom, and especially in the textbooks I was reading. Converting these notes into brief commands that could then be shuffled and randomly selected as a part of my process has become increasingly important to my work. Everything about my process moves between being highly structured and regimented, and being random and unexpected or uncontrolled. Acting within these extremes opens up opportunities to rethink and reconsider what seem like “givens” so the results can embrace ambiguities and ambivalences in perception and interpretation. It also acts to minimize and challenge my own authority to determine the result, creating situations where the audience can engage in the same visual play with perceptions that interested me when I was making the work: this invitation to creatively engage the motion picture invites the audience to engage with the same process-of-seeing used to make the work in its reception.

The generative outputs of digital animation, compositing, photography produce footage that is uniformly subject to the vagaries and manipulations of encoded and compressed data. My process is concerned with retaining control over the results rendered through glitch processes, while at the same time ceding the precise details of what appears on-screen to the autonomous operations of the computer: this is not a paradox, but a conscious choice to set up specifically abnormal conditions whose determinate outputs can be generally anticipated, and then allow the machine to operation normally within them, capturing the results in the same way that live action filmmaking captures its dailies. These “shots” are not the end of the process, but the middle: they come in-between the planning stages of preproduction (which often includes the pre-editing of shots and materials to glitch) and the complexities of assembly in post-production. But unlike live action where the performance recorded will never precisely repeat, the glitch processing creates variations, complexifications, and elaborations on the same footage—a whole family of alternative tangents derived from the same source. Glitches become more elaborate by taking one and glitching it a second, a third time, or more to accumulate changes—which can be saved independently at each stage of the procedure to allow for their later fusion via editing and compositing software. This looping makes my process a conscious analogy to the mechanical procedure of video feedback, an amplification of minute details.

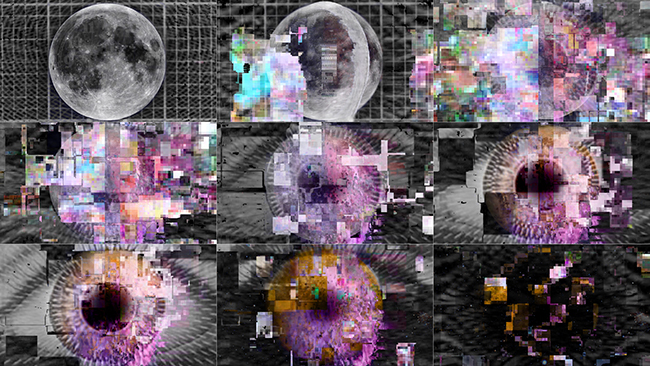

How I select and arrange my materials (both shots and parts of shots composited together) is guided by creating and maintaining the tension between these poles. At low levels, glitching is simply an interruption or deviation from what remains fundamentally representational footage—a momentary slippage of its realism—but at higher levels, the glitches become a new form of procedural animation, generating entirely new images and movements without reference to whatever imagery there might have been before. My working process involves creating these transformations, but also looking at them in relation to each other so I can modulate and manipulate their combination and confusion. I usually begin with some piece of footage that strikes me as iconic in some way that evokes a particular cultural image: my interests in the visionary tradition guide what kinds of imagery I choose. This similarity renders that starting point as already a variation around which the glitches can proliferate (variability as a formal principle) in a range that becomes increasingly abstract and untethered from the initial iconic image. My selection process is utterly subjective: looking for this iconic connection is a way to bring content into the movie apart from the material handling of the footage. The process, then, becomes the constructive balancing between familiar iconicity and unfamiliar abstraction, moving between them as the progression and action of each shot—no matter what else is going on with its semiosis.

These methods for making ultimately have nothing to do with what it means; they are “blank,” open to any content that I wish to express through them. I have found this undefined quality for glitches allows them to act as expressive medium comparable to analogue video or celluloid, one that devolves from those capacities particular to the digital. My process attempts to mobilize these capacities, to acknowledge digital technology as a resolution to the historical oppositions between ‘live action’ and ‘animation,’ realism and abstraction, artificial and natural through transformations that center perception as a proximate and immediate activity.

Copyright © Michael Betancourt February 25, 2022 all rights reserved.

All images, copyrights, and trademarks are owned by their respective owners: any presence here is for purposes of commentary only.