from Cinegraphic.net:

FYI: a Partial Pre-History of Glitch Art

story © Michael Betancourt, April 27, 2023 all rights reserved.

URL: https://www.cinegraphic.net/article.php?story=20230427080328586

Glitch Art has claimed an extensive history of precedents and sources throughout both art history and media art. The contemporary use of digital glitches as a source of aesthetic and expressive imagery emerges from the lineage of avant-garde exploits of media and technology in the early twentieth century, and before that, the concerns of the Arts and Crafts movement with demonstrations of the 'human hand' in art making during the nineteenth century.

This small (and incomplete) selection highlights artists working at the end of the twentieth century who were employing glitches self-consciously in their work, but were active before, or apart from, the later social media groups on Flickr and Facebook that consolidated and brought the idea of glitches-as-art into general public consciousness. It should not be considered an exhausive, final or even complete presentation of the early artists pioneering glitches and Glitch Art, but is instead offered as a sampling of the kinds and range of works being done.

Although both Len Lye and Norman McLaren worked with scratches and direct animation during the 1930s and 1940s, and their work inspires contemporary Glitch Artists, neither filmmaker presented their work as an engagement with failure or glitches. This later association of their work with Glitch Art comes despite their own claims about using direct animation as an expressive means that allowed a personal engagement with the film strip itself; theirs approach should be understood in context with other formalist concerns for the materiality of the medium—which for film meant celluloid and the intermittent projection of images. Their re-invention of the process of direct animation pioneered by Futurists Bruno Corra and Arnaldo Ginna between 1909 and 1912 is not a product of courting disaster, as in later Glitch Art, but a direct result of attempts to fuse the immediacy of painting with the procedures of animation.

John Cage's prepared piano compositions provide a reference point for Nam June Paik's invention of the modified television set, which was rewired and altered to produce fragmented and distorted imagery that converges on the reception errors identified in repair manuals for television receivers in the 1950s and early 1960s. This engagement with the distortion of reception—a technique commonly employed by glitch artists who work with analogue technology—has an extensive history in video art that anticipates the later emergence of Glitch Art itself in how artists engaged with the materiality of digital media starting with the appearance of digital video games, and then the personal computer. The popular expansion of the internet during the 1990s and increasing power of both computer and the then-new digital video cameras made the wide-spread embrace of glitches by visual artists a logical continuation of earlier approaches to media from the earlier twentieth century.

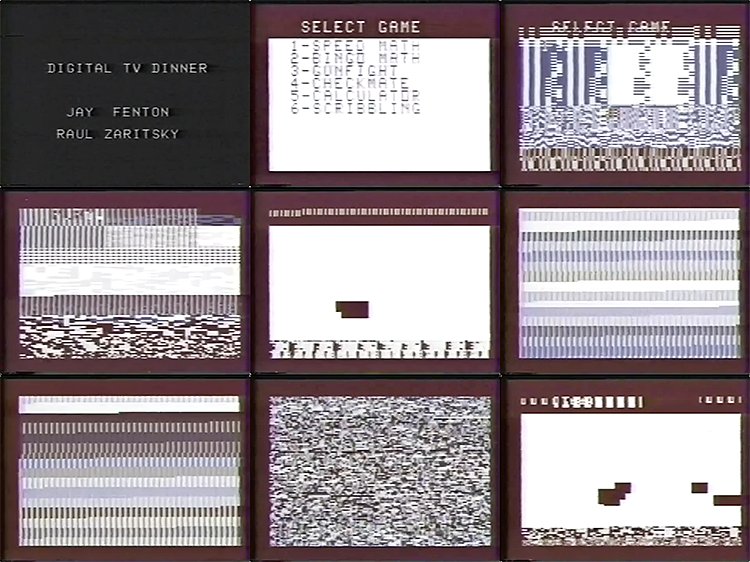

Fenton worked as a video game programmer on the Bally Astrocade console, and made Digital TV Dinner, produced in two versions in 1978 and 1979, by exploiting her knowledge of that system. It is the first work of Glitch Art that specifically employed digital breakdowns and errors for aesthetic purposes—making a video that demonstrates these breakdowns reflexively and directly. This work was initially shown at the “Electronic Visualization Event #3” organized by Dan Sandin and Tom DeFanti’s Electronic Visualization Laboratory in May, 1978, broadcast on television in March 1979 on the WTTW program Image Union, and that version of the piece was eventually uploaded to YouTube in 2009 when it was recognized as the starting point for Glitch Art. Its use of video games and the performative nature of the glitching anticipates many later processes in common use.

Digital TV Dinner (1978)

Scott created the term "Glitch Art" on his website in July 2001 to describe the kinds of digital interventions he was doing that created highly geometric abstractions he had been generating from computer breakdowns and hacking software since the 1980s. These purely digital works combined programming with visual art. He brought his performance based works to the Glitch Festival and Symposium in Oslo, Norway that took place in January 2001, and he was an editor on the Glitch: Designing Imperfection book that collected work by artists engaged with glitching in 2003 (pubished 2009). His work began integrating digital glitches with more traditional analogue media in 2005, producing photograms by placing sheets of black and white photo paper on a computer monitor to make a contact print of his digital images.

Skyscraper #1 (2005)

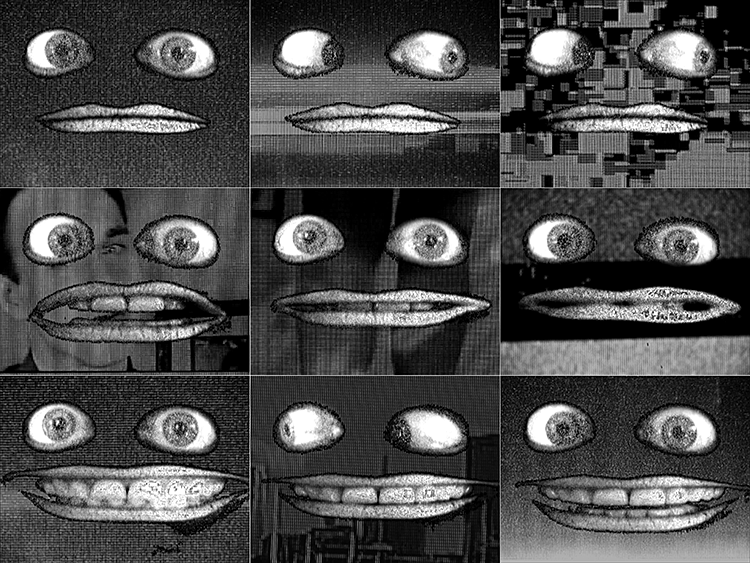

Recher's employed film and video as a theatrical performance, presenting what he termed "cinematic mantras" where glitches served as reflexive interruptions to what was happening in the piece. Early works such as Snafu (1981) involved a film shown in the window of a movie theater's projection booth, presented after the film broke and interrupted the screening that was happening, or No (1989) which combined a film loop of Marilyn Gottleib-Roberts saying "No." that visibly stuck and jumped in the projector with a video monitor of her asking if she wanted a wide range of things. He began using digital glitches in his January 2001 performance TV shown on Miami Beach's Lincoln Road Mall as part of the Florida/Brazil Festival. The digital interruptions in TV provide a backdrop for the cartoonish eyes and mouth that talk about the amoral dominance and power of media.

TV (2001)

malfunction (2000)

Her work with glitches involved the exploit of analogue-to-digital lapses and encoding errors in a reflexive amplification of her concerns with body and representation that informed her earlier performance art. Her work employs glitches in an anticipation of their more contemporary understanding: as a Feminist challenge to the gaze and heteronormative visual encoding in videos such as The Bride or Delicate Cuttings (both 2002). By using imagery that invokes voyeurism and the iconography of the feminine, Hall employed glitches as a way to interrupt and fragment those systems of visual presentation.

Delicate Cuttings (2002)

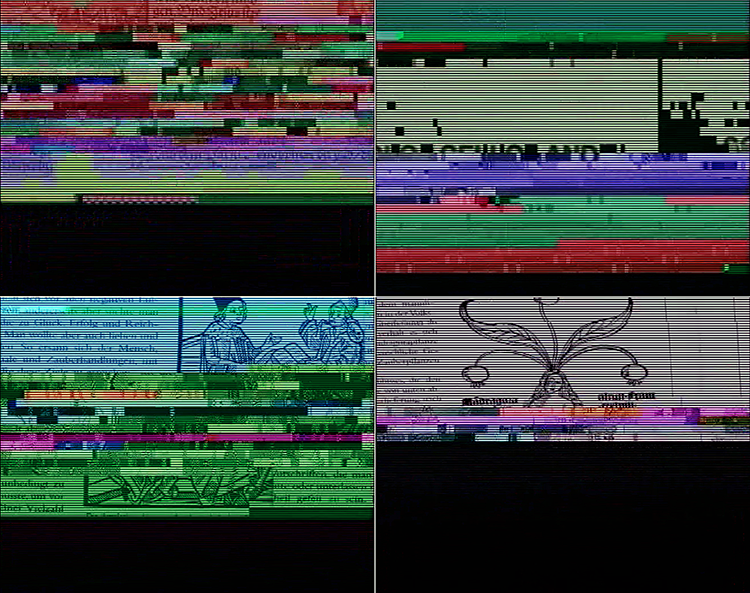

The best known glitch video from artist duo Renata Oblak and Michael Pinter-Koschell is the video zijkfijergijok (2002) made from databent and corrupted jpegs that have been used as the frames for a video. Their works interrogate the nature of communication, and employ glitches as a way to interrupt that process.

zijkfijergijok (2002)

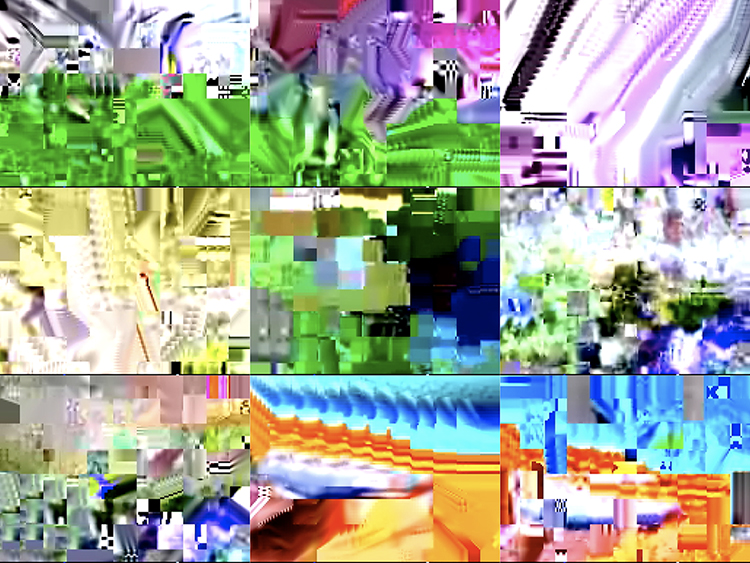

Murata is a pioneer of datamoshing, a process that removes data from digital videos compressed using the MPEG-1 format, resulting in characteristic smears of color and residues from the original image on screen. Also known as "frame compression," it is an exploit of how digital video encoded as MPEG compresses video data that involves altering this information selectively. Murata made several videos with this technique, including Monster Movie (2005) and untitled (Pink Dot) (2007) where the technique is the primary material of the video; later works such as Shiboogi (2012) integrated these glitch processes with other unglitched imagery.

Monster Movie (2005)

Copyright © Michael Betancourt April 27, 2023 all rights reserved.

All images, copyrights, and trademarks are owned by their respective owners: any presence here is for purposes of commentary only.